Dedicated to my precious husband and my remarkable 5 children. May my ceiling be your floor.

The White Flight and United States Education

After the 2020 census, (United States Census Bureau, 2020) there was discussion that prompted the reconfiguration of redistricting the public school sector. This led to a significantly increased analysis of race, curriculum, and the wealth gap, amongst many other politicized topics (Democracy Docket, 2023). While the issue of present-day segregation entangles many of these variables to include discrimination, income disparities, and redlining are noticeably maintained through the process of gerrymandering. Ideally, the post-Brown v. Board of Education was an open door to phase out segregation with redistricting opportunities that would increase diversity in public schools. This, however, was never brought to completion, leaving many schools susceptible to less funding, high dropout, and low graduation statistics (Madeline Will, 2019).

This study is an in-depth look at the historical and sociopolitical climate on how political funding, influence, and involvement lead to gerrymandering and result in curriculum vulnerability. The psychological effects of these variables have a significant impact on either the success or failure of literacy. The consequence of educational disparity is vast and results in a lack of empathy toward generationally impoverished groups. In addition, capital is withheld from these groups, which prevents long term change.

Post Civil War Timeline

1862 – Although education for Blacks was highly controversial, for White taxpayers, it was not overlooked. Moving into the Civil War, on July 2, 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed the Morril Act promising a state minimum of 90,000 acres of land to sell to establish colleges of engineering, agriculture, and military science. Proceeds from the sale of these lands were to be invested by the government in a perpetual endowment fund that would provide support for colleges of agriculture and mechanical arts in each of the states (Hartman, 2022). This is one of many racially disproportionate decisions to advance the education and capital of White families while resulting in a negative outcome of Black Americans.

The post-war efforts for educational control were not only found in government legislature but in non-profit work with the “United Daughters of the Confederacy” (Chamberlain, 2022). The Daughters of the Confederacy played an integral role in the “Lost Cause”, an academic movement that revised history to be more favorable to the South after the war ended. These women leveraged their social and political power from antebellum families to fundraise and erect monuments that memorialized Confederate soldiers. They also created review boards to audit what Southern children learned about the war.

The Civil War marked a turning point in Black education in the Southern states. Soon after the breakout of the war, there emerged in the South, for the first time since the enactment of the anti-literacy laws, unconcealed efforts to establish and maintain Black schools.

1896 – After the American Civil War (1861-1865), most southern states and, later, border states passed laws that denied Blacks basic human rights. This changed one day in 1892 when a man named Homer Plessy stepped onto a White person-only streetcar. The Louisiana Separate Car Act made him a criminal and he was arrested and tried by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court rejected Plessy’s argument that his constitutional rights were violated, and the Supreme Court ruled that the law “implies merely a legal distinction” between White people and Black people was not unconstitutional (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896). As a result, restrictive Jim Crow legislation and separate public accommodations based on race became commonplace.

Plessy v. Ferguson opened the door for accepting marginalized and often deplorable conditions for Black education. The law stated, “separate but equal,” however this law brought inconsistency and a disproportional amount of attention to Black schools from its conception. Black communities found their schools underfunded as compared to their White counterparts. The many variables, including redlining, that enabled White families to move out of the cities to the suburbs and build new homes in the White neighborhoods. This left Blacks with less funding and accommodation for their homes and businesses.

The White Flight

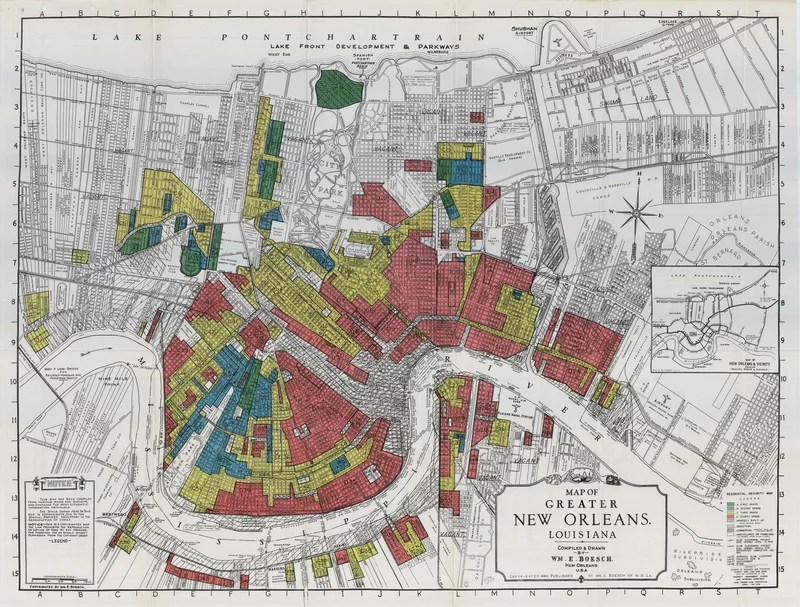

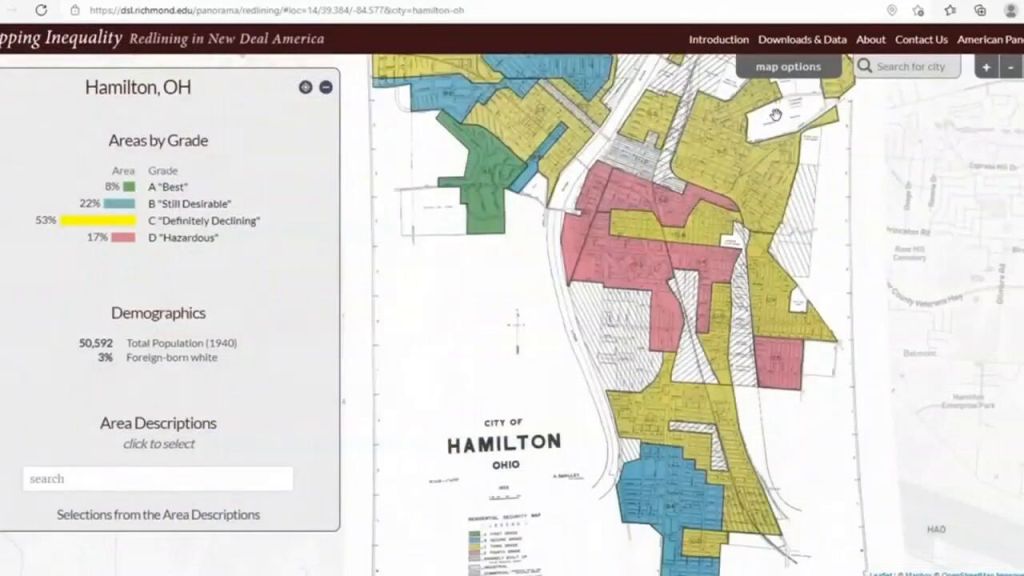

1933 – Redlining was established by the government. Real estate agents would color neighborhood maps ranging from green for “Best” to red for “Hazardous,” this came to be known as “redlining.” Redlining ensured funding to White neighborhoods and grossly underfunded African American neighborhoods (Boustan, 2013). This consequentially reinforced negative stereotypes about non-White neighborhoods and directly limited access to home ownership and business development in those neighborhoods which has generationally led to hyper-ghettoized communities that still exist to this day (Boustan, 2013).

Shortly thereafter, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) began insuring home mortgages for White-only neighborhoods in 1934. In addition, the FHA favored loans for new suburban construction over older urban properties, simultaneously contributing to urban decay and the growth of White suburban neighborhoods, while discriminating against Black/African American and other non-White communities (Boustan, 2013).

1938 – In a continued discriminatory fashion, Congress created the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) which severely limited African Americans’ access to mortgages. The language enabled a significant boost to White homeownership levels by making low-cost loans widely available, however only offering a fraction to Black families. $120 billion in new housing subsidized by the federal government was given between 1934 and 1962, providing manageable mortgages and housing opportunities for young families, to which only a significantly small percentage went to Black families.

1944 – The GI Bill promised many benefits for service people returning from World War II, including low-interest home loans. Once again, the program’s structure prevented people of color from fully accessing these benefits. As a result, Black veterans were deprived by the government of the benefits of the post-war housing boom which became a key source of generational wealth for White middle-class families. The FHA and VA financially backed these housing initiatives despite the use of racially restrictive covenants that prevented home sales to non-White people (Blakemore, 2023). Many Black men returning home from the war did not even try to take advantage of the bill’s educational benefits as they could not afford to spend time in school instead of working. The few who did were at a considerable disadvantage compared to their White counterparts. Many Black Americans lacked much educational attainment due to poverty and social pressures.

As veteran applications flooded universities, Black students often found themselves left out. Before the GI Bill, the Morrill Act of 1890 also had complicated consequences of contributing to the segregation of educational facilities. PWIs (Predominantly White Institutions) were receiving funding and appropriations some twenty-six times more than HBCUs (Historical Black colleges and Universities) (Bracey, 2017). This left Black schools grossly disproportionally funded. Northern universities dragged their feet when it came to admitting Black students and Southern colleges barred Black students entirely. A full 95% of Black veterans were shunted off to Black colleges and institutions that were underfunded and overwhelmed by the influx of new students. Most were unaccredited, and with a massive influx of applicants, they had to turn away tens of thousands of veterans. In addition, the VA encouraged Black veterans to apply for vocational training instead of university admission and arbitrarily denied educational benefits to some students (Bracey, 2017).

1949 – The American Housing Act greatly expanded the federal government’s role in housing. It included significant funding and authorized the use of the eminent domain to clear slums, paving the way for urban renewal in the subsequent decades. By 1974, 2,100 urban renewal projects covering 57,000 acres had been completed totaling $53 billion. In the process, 300,000 families were forced to move – more than half of whom were non-White (Collins, 2013).

Before the post-Plessy v. Ferguson systemic integration, so much of life was provided for Whites to enjoy with these policies. Pools, parks, and zoos were all free. These once social privileges opened to people of color were taken away with pools, for example, being quickly filled with concrete. Public pools became private country clubs in suburbs where one had to pay a fee to join. Parks closed and moved out of red zones where Blacks could not access them, and theme parks became much more expensive. State’s rights were heavily pushed by political forces attempting to legally make it impossible for people of color to own property and close the wealth gap (McGhee, 2021).

Pictured is a hotel manager pouring acid in a pool with Black Americans, 1964.

1940 – 1980 – Over the course of forty years there was a dramatic expansion of the homeownership rate among urban African American households. Three-quarters of this increase occurred in central cities during the White flight to the suburbs. In 1940, 19% of Black households living in urban areas were homeowners. By 1980, the metropolitan Black owner-occupancy rate had risen to 46%, an increase of 27% (Boustan, 2013). All of these historical markers continued to push families of color into a hyper-ghettoized state, preventing Black Americans from focusing on education as White families could. There were not as many public schools available for Blacks. If a town did not have enough money for two separate schools, they built only one school – for White children. This was especially true in the rural towns as they lacked the most funding. There was a significant contrast between urban and rural living, particularly as it pertained to access to education for Black children. Metropolitan school systems had more money than rural. However, in the post-Civil War South, most African Americans resided in rural areas continuing to work as sharecroppers on farms. Prior to the White flight in the mid-20th century, White children lived in cities and could attend well-funded city schools. In rural areas, schools for both Black and White children were scheduled around the cotton growing season. African American children were often pulled out of school to collaborate with their parents on the farm in order to meet the demand for sharecropping. White farmers’ agricultural needs took priority over the education of Black children where White families had the authority to pull their children from schools. This consequently led to fewer months per year for Black children to focus on education.

Black schools were often left to decay with sagging floors and windows without glass and were left in filthy conditions. Textbooks were hand-me-downs from White schools filled with racial slurs. Because of a lack of funding, classrooms were overcrowded with ages from pre-school to eighth grade in one room (Brooker, 2022). In addition to withholding appropriate means to facilitate a classroom, there were also limits to what Black children could be taught. Words such as “equality and freedom” were discouraged, and some Black schools did not permit books that included the Declaration of Independence from the Constitution (Brooker, 2022).

St. Paul Chapel Rosenwald, all White school, VA.

School for Black children. Halifax County County VA,1930.

Black families also often paid a “Black tax” or a double tax because they had to pay local taxes and use their funds to support their underfunded Black schools. Black teachers, who were paid not only a minimal salary, found payment by way of eggs, or other items Black families could leverage. Black teachers also knew that their duties went far beyond academic instruction; they were often required to use their funds and work outside school grounds to help their students both inside and outside the classroom (Tyack, 1986).

1954 – The U.S. Supreme Court declared, “in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and ordered the desegregation of the nation’s school systems to integrate. The 1954 ruling extended to all domains of public life and “established equal protection for Blacks in housing, voting, employment, and graduate study” (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 1954). Nevertheless, Brown did not stop some White Americans, particularly in the South, from dismissing this integrative ruling, as racial discrimination continued to occur at all educational levels in the United States. Advocates of White supremacy and White segregationists, like the late George Wallace, once the governor of Alabama, pledged “to stand in the schoolhouse door to prevent the enrollment of Black students at the University of Alabama” (Leffler, 1963).

Prior to Brown, in the seventeen states that had segregated school systems, 35 to 50% of the teaching force was black (compared to 7% today) (Will, 2019). Although Black schools were under-resourced or underfunded, many Black teachers received scholarships through Northern Universities to earn master’s and doctorate degrees. One of the downfalls of Black education after Brown was the displacement of Black educators (Will, 2019). Many White teachers had lower expectations for Black students which set the stage for underperformance on standardized tests limiting future opportunities. This was a huge change in pace from Black teachers who were seen as role models within their communities (Irvine, 1983). Among the challenges with inconsistencies in academia, there was also a disproportionate level of discipline for Black students. This developed a distrust of White authority that contributed to the marginalization of the Black population, however, continues to benefit Whites to this day.

With redlining and other variables that contributed to the White flight, Blacks were forced into subsidized housing and deprived families of property ownership opportunities. In 1956, during the beginning discussions of redistricting, the National Interstate Defense Highways Act funded the construction of a $25 billion project that would take upwards of 10 years to complete. The United States highway system was the largest public works project in US history. Controversial from its conception, many people were concerned about the impact the “concrete monsters” would have on historic districts, parks, schools, churches, and waterfronts as well as alter natural landscapes (Biles, 2014). The opposition and protest of a clear path through neighborhoods, which were predominantly people of color, made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. It was eventually decided by the justices, “alternative routes undoubtedly would impose hardships upon others, further asserting that such weighing of hardships in road design is a task for engineers rather than a judicial body” (U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Sixth Circuit, 1967). Within a year of the project’s first completion in Tennessee, most businesses in the neighborhoods surrounding the road had suffered financially and some closed while property rates declined by a third (Tennessee State Museum, 2014). As Raymond Mohl (2014) describes:

Eventually, the I-40 expressway demolished more than 620 Black homes, twenty-seven apartment houses, and six Black churches. It dead-ended fifty local streets, disrupted traffic flow, and brought noise and air pollution to the community. It separated children from their playgrounds and schools, parishioners from their churches, and businesses from their customers. (p. 880)

Unfortunately, this scenario was not specific to Tennessee. In Miami, for instance, highway construction captured forty square blocks of city space, demolishing some 10,000 homes and a predominantly Black business community (Mohl, 2008). The impact in Detroit was similar, as the route of the highway tore through minority communities and left behind large swatches of cleared neighborhoods (Biles, 2014). There, as in many other cities, highway plans were announced long before construction would begin, resulting in significant drops in property values for Black communities. This project displaced thousands of Black families and further impoverishing the residents of these neighborhoods who were mostly Black, Indigenous, people of color, or immigrants.

As a result of the US Highway, redistricting Black neighborhoods doubled down on devaluing their community values offering fewer property taxes to fund education.

The White flight continued with the opening of segregation academies (private schools). One of many examples was in the town of Smallville Louisiana in 1969 when the federal court ordered the first four grades to integrate Black and Brown, students (Champagne, 1973. Pg 61). A parent stated they would hire a private teacher for his White child to prevent integration. This led to an influx of parents collaborating, creating a building fund, hiring the principal from the public school, and eventually bringing the teachers on board as well. The Smallville Academy was brought to fruition. Private schools around the country became a legal means to bypass integration as well as pull money and resources from public schools that instructed students of color. Over time, the concept of the “private” sector became the essential means segregationists used to continue systemic racism in the US (Champagne, 1973. Pg 63).

By 1970, over three hundred segregation academies were created with some 500,000 White students attending (Giles, 1974. Pg. 1). With declining White enrollments in public schools, many schools were forced to discontinue extracurricular activities and enrichment. In addition, their schools declined with an inadequate teacher-to-student ratio and overcrowding became an issue. In many instances, schools were forced to close together due to a lack of funding. It was not until the Runyon v. McCrary case in 1976 that the McCrary and Gonzalez families sued Bobbe’s school and Fairfax Brewster School, White-only private schools, for discrimination based on race. The Supreme Court Ruled in their favor and private schools were forced to integrate children of color thereafter or lose tax-exempt status (Runyon v. McCrary, 1976). This, however, does not come without its own set of challenges for families of color not only finding transportation to private schools but affording the many other amenities within private schools as well as maintaining the same academic requirements with limited resources available.

Bussing also played a complicated role in the White flight. Bussing can be costly and absorb substantial portions of a school budget. However, due to redlining and segregated communities, it was necessary for the integration of Black students in White school districts. Transportation was a significant contributor to White families moving out of once popular school districts costing districts the funding needed for bussing leading to other financial challenges (Giles, 1974. Pg. 1).

Psychology of the Wealth Gap

Since the full integration of schools in 1976, we have seen a consistent generational wealth gap because of our history’s systemic segregating practices. The United States 2020 Census Bureau states Non-Hispanic White households had a median household wealth of $187,300, compared with $14,100 for Black households and $31,700 for Hispanic households. These specific numbers lead to a large inadequacy in education due to its effect of psychological and sociological consequences on the families that live in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

In 1943, Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, proposed the idea of a “Hierarchy of Needs” which hypothesized that if human lower-level deficiency needs were not met, higher-level growth needs would be impaired. (Maslow, 1943) He created a visual illustration to explain his theory.

He hypothesized that there are five basic needs—arranged in a hierarchy from lower order to a higher order—and that all these needs are essential for optimal human development (Maslow, 1943). The bottom three tiers illustrate deficiency needs whereas the top illustrates growth needs. Maslow argued that although deficiency needs are the initial and primary focus of human lives, after these needs are met, higher level and less physiological needs emerge and become a driving force for the individual. Each step is imperative for cognitive and psychological growth and if a person experiences trauma at any given stage of deficiency, their body will default to survival mode, sacrificing a growth of the top two tiers in order to devote cognitive and emotional resources to surviving the traumatic event. Any traumatic event can leave emotional and psychological scars, which is referred to as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Individuals with PTSD can have symptoms that last long after the traumatic event took place. Fortunately, there are treatments available (most often only available to those who have a larger disposable income) that can bring relief to these often-debilitating symptoms of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Another type of PTSD is Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which a described as a complex behavioral condition in survivors of prolonged or multiple traumas, where trauma escape is difficult or impossible, and entails changes in affect regulation, consciousness, self-perception, and relationships with others, among other symptoms. In other words, a system of trauma that one does not escape that keeps the nervous system in a state of fight, flight, freeze or fawn, or survival mode. The long-term effects of this type of trauma can prevent the quality of life for the victim as it pertains to personal relationships, social settings, educational ability, work-related challenges, or other critical areas of functioning in everyday life. PTSD and C-PTSD prevent rational thought and inhibit the ability to access the prefrontal cortex of the brain to critically think and or correlate information.

Statistically speaking, those who live in poverty, or hyper-ghettoized, marginalized conditions, experience a disproportionate level of physical and sexual abuse in addition to housing and food insecurity (Tjaden, 1998). All these experiences can lead to PTSD and C-PTSD, yet there is still a demand for children and even adults in higher education, to achieve academic success despite their living in a state of survival mode. When considering the intersectionality of trauma and Maslow’s theory of what leads to success within capitalism, let’s combine the two variables to create a clear picture of who is most likely to maintain the level of deficiency needed to create growth and even succeed in self-actualization.

Per the psychology of Maslow’s hierarchy in correlation with the wealth gap, those who experience the most trauma stemming from abuse, food insecurity, housing insecurity, and other variables, compromise the brain’s ability to function. To achieve self-actualization for those who experience life on the bottom three tiers, or the deficiency tiers (D-needs), those whose life experiences echo the top two tiers, or the growth or being needs (B-needs), must supply equity and capital. Capital can be defined as many variables in this case such as financial investments, community, family, mental health, quality health care, quality education, extracurriculars, hobby groups, and other means to develop refinement of oneself. These variables of capital lead to a greater ability to contribute to civilization and generate wealth equating to higher self-actualization within a capitalist society. Without the equity provided, the bottom D-needs tiers will continue to live in a state of fight, flight, freeze, or fawn from deprivation of basic physical and psychological needs. This prevents appropriate healing of the brain and body to produce what is needed to assume value within capitalism and severely limits those who live on the bottom D-needs tiers. Often, despite the significant financial and mental health deficiencies, the same expectation of health and performance is required of the D-needs tiers as their top-tier peers. For instance, in the case of a catastrophic loss, an individual experiencing trauma living in the B-needs tiers would potentially have a community to provide meals and support, family, monetary means, mental health care, and past positive life experiences to bring a sense of hope. If the same catastrophic loss is experienced for someone who lives in the bottom three tiers, there is significantly less support, they are potentially more isolated and surrounded by others who are experiencing similar trauma and have less capital to give, as well, there is less monetary wealth for mental health care, fewer education opportunities, and low paying jobs. These psychological and physical deficiencies greatly effect health and performance, yet the same expectation of growth and development is expected. Without the ability to monetarily contribute to our capitalist society and meet the top tier of expectation, capital is frequently withheld from the D-needs group as a negative incentive to achieve self-actualization and contribute to the GDP. This behavior causes polarization of the bottom D-needs tiers, can lead to further isolation, and additional financial loss, can significantly impact mental health, and continues a state of flight, flight, freeze, or fawn, causing a larger divide from the top and bottom tiers. The psychological consequences of the wealth gap are significant enough that the amount of capital for any one individual to move only two tiers up can take generations of investment, therefore any further overt or microaggression that can lead to isolation is dire.

Ultimately, the more investment of capital and equity to the bottom D-needs tiers from our nation’s churches, community groups, school systems, and government, the economically stable our country will be.

Social Emotional Learning

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions (CASEL, 2013). This type of emotional intelligence and self-regulation is correlated with social competence (McKown, 2009). Among typically developing children, the ability to make mental state inferences is positively associated with teachers’ reporting of more frequent competent and less frequent aggressive and withdrawn behavior, better teacher-reported interpersonal negotiating skills, and greater peer regard. Similarly, greater verbal ability is associated with more frequent teacher-reported competence and less frequent aggression, which are in turn associated with peer regard. In addition, the better children perform on measures of SEL skill and the more their parents and teachers report that children can regulate their behavior, the more competent their social interactions are (McKown, 2009).

In contrast, multiple complex-traumatized children, or children who suffer from CPTSD, frequently fall through the cracks in our healthcare system. These children are often hospitalized with different treatment approaches for different diagnoses due to a lack of a comprehensive understanding of their emotional experience and its processing (Hug, 2022). Very early, unprocessed trauma, common in multiple complex-traumatized children, may continue to have an impact in subsequent developmental stages as “cumulative trauma” (Khan, 1963). Therefore, dealing with trauma in a secure relationship after traumatization is crucial to avoid re-traumatization, pathological adjustment, or developmental arrest (Hug, 2022). This significantly weighs the importance of SEL for regulation and class management.

SEL has resulted in significant success in classroom management for both typical and neurodivergent children. Self-emotional regulation benefits both teachers and students which leads to a calmer classroom to then focus on academic STEM material. When looking at Maslow’s pyramid, although typical developing children benefit from self-regulation tools, there is a strong correlation between children of color and those who live in survival mode and trauma.

Without the ability to self-regulate, not only will they have less of an opportunity for success, but their peers also have the potential to suffer academically from disruption. SEL is developed to consider all of these variables to provide the most enriching learning experience possible in the classroom for both teachers and students.

In 2021, new anti-SEL theories developed attempting to ban its instruction. Contrary to the scientific benefits of classroom management and self-regulation, Teresa Dewitt, a speaker, and writer for the group, Moms of Liberty, states:

“In short, they are expected to believe the highly controversial hypothesis that America is awash in “systemic” and “structural” racism, and that only massive government-led social engineering can fix it. The children are also expected to accept and agree with the artificial divisions being fomented along “race” and “class” lines as a part of the now obvious effort to “divide and conquer” America… It’s extremely dangerous.”- Teresa Dewitt, 2021

She also referenced SEL as a tool for “Anti-White racism”. Many also subscribe to the school of thought that self-regulation should be left at home and not in schools. There are many challenges with this ideology. By Feb 2023, single motherhood had grown so common in America that today single mothers head 80% of single-parent families — nearly a third live in poverty (Michas, 2023). 79.5% out of 10,889,000 were female lead single parent homes, 23.4% were under the poverty line, 24.3% were experiencing food insecurity and 62% of all that receive food stamps in the United States go to single mothers which concludes these are scientific moderate to strong statistical findings (Census.gov, 2022). Of these statistics, families headed by women of color fared disproportionately even worse. Two in five (35%) of Black female-headed families lived in poverty, a close second is Hispanic female single family homes at (34%), White (26%), and Asian (22%) (Census.gov, 2021).

An example of outcomes of families living in poverty and its impact on academia can be proven through evidence in school districts in the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area. No matter their age, a significant percentage of Cincinnati’s schoolchildren live in poverty. Of students in grades one through four, 45.6% are categorized as living in poverty. That number decreases in middle school (40.1%) and high school (38.1%) but rebounds in college to 48.5% (Federal Register, 2023). In correlation, the Ohio School Report Cards rated their achievement, progress, gap closing, and early literacy two out of five stars stating they “need support to meet state standards” as well as demonstrated “significant evidence the district fell short of growth expectations.” The most concerning variable however was the graduation rate which received one out of five stars (Ohio School Report Cards, 2023). In addition, 78% of the student body is a minority, significantly more that the Ohio average of 32% minority (Public School Review, 2023). These statistics are consistent with the data on the pyramid pictured above and correlate with the importance of continuing SEL to assuage the need for classroom management with children who are victims of trauma.

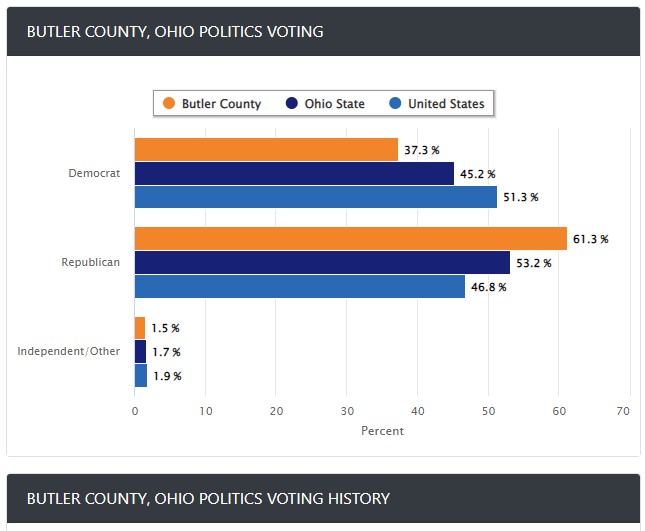

Despite the negative narratives of SEL in sub groups of leadership, many believe SEL has a place in the US education system. A sample study was taken by the author from a social media page for a local school district outside of Cincinnati to determine their cognitive understanding of factors that affect mental health. In addition, another survey was conducted by the author for the sample population to express their opinion of having SEL available in the classroom for their students. The school district is based out of Butler County Ohio with 37.7% Democrat and 61.3% Republican.

Photograph is taken by the author from bestplaces.net.

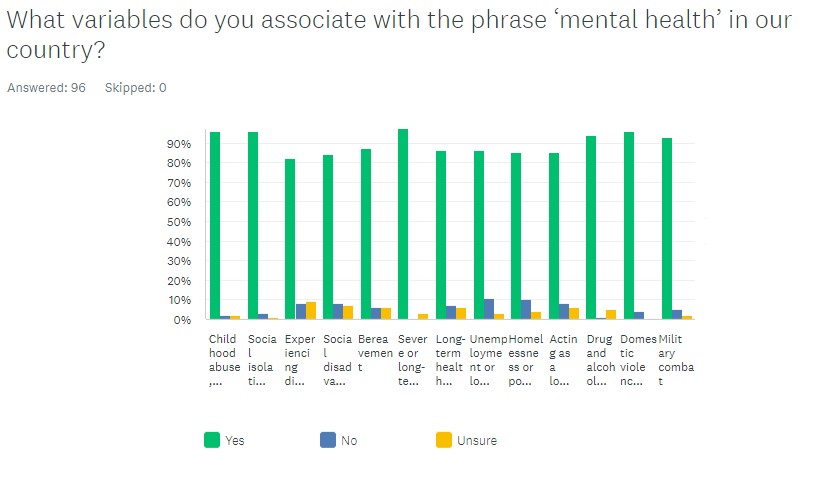

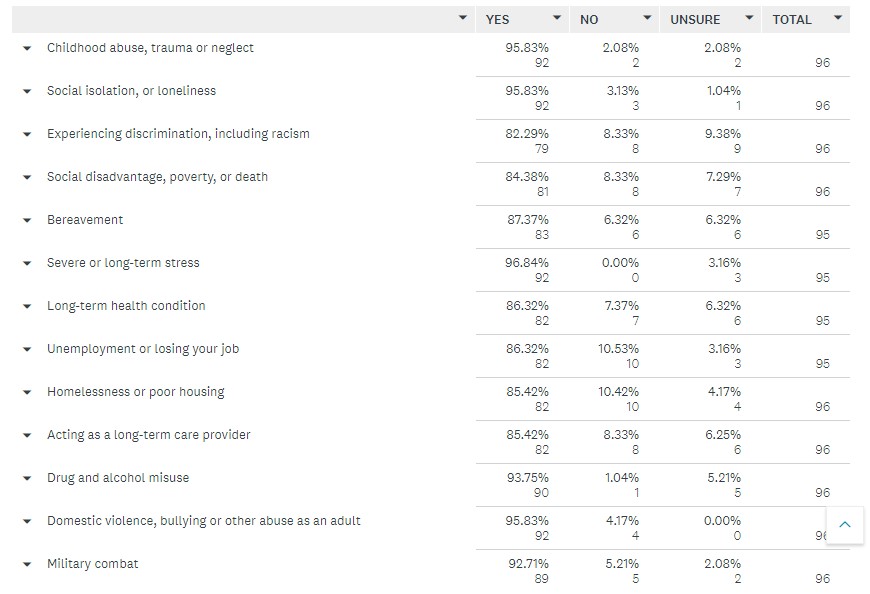

97 adults responded, ages 18+, and 88.89% were White. Their first question was to define Social Emotional Learning. The identifiable keywords that were significant consisted of “self-awareness, empathy, cognitive development, potential, kindness”. The second question was whether the participants in the survey agreed with the implementation of SEL within their school district and 81% said yes. The second survey was to determine if the sample population associated variables that significantly affect mental health with the phrase, “mental health”. 79 adults, ages 25+, 98% White took the survey. The variables on the survey that significantly affect mental health per the American Psychological Association were as follows: Childhood abuse trauma or neglect; Social isolation, or loneliness; Experiencing discrimination, including racism; Social disadvantage, poverty, or death; Bereavement; Severe or long-term stress; Long-term health condition; Unemployment or losing your job; Homelessness or poor housing; Acting as a long-term care provider; Drug and alcohol misuse; Domestic violence; Bullying or other abuse as an adult; Military combat. This was to determine the cognitive understanding of Maslow’s hierarchy of Needs from the general population and its potential effect on mental health in each tier.

Here are the results.

The conclusion from these sample studies is that a significant portion of the population can identify and agree with the implementation of SEL, as well, as can identify and understand significant factors that can correlate with mental health.

Critical Race Theory

Another area of political tension is the discussion of Critical Race Theory. Webster’s Dictionary defines CRT as, “a set of ideas holding that racial bias is inherent in many parts of western society, especially in its legal and social institutions, based on there having been primarily designed for and implemented by White people.” CRT has become the center of debate in conjunction with SEL. Political sub groups in Indiana argue that SEL has become a “Trojan horse” for critical race theory stating it’s part of a ploy to “brainwash” children with liberal values and to trample parents’ rights (Kingkade, 2021).

CRT is a college post-graduate level course and despite this data point, there are curriculum audits all over the country to prove CRT exists in schools in hopes to remove literature about the history of people of color similar to House Bill 266, and 999 in the state of Florida. These tactics are consistent with the original means of marginalizing education for people of color in our country and also to deprive White children of academic opportunities. Buzzwords such as “diversity and inclusion” immediately stir arguments of “White oppression” (Poussaint, 1979). Contrary data, however, when viewing the history of the wealth gap and education in the US, White families hold twenty times more wealth than people of color.

Lakota Schools

Like many areas of the United States, Cincinnati’s neighborhoods rapidly changed over in the mid-20th century. As is the case for most American cities, the Queen City fell victim to the “White flight” causing many historically White neighborhoods to quickly turn predominantly Black. They saw the development of highway projects and continual gentrification forcing Black families to settle out of White areas. “The neighborhood of Evanston for example had a total population of 12,261 people in 1950, 968 of whom were Black. By 1960 the total population had increased to 13,740 and the Black population had ballooned to 10,278,” according to UC Libraries’ T.M. Berry Project. In a single decade, Evanston’s Black population skyrocketed from 7.9% to 74.8%, and White flight did not allow “integration” to last long (Reller, 2011).

During this time of rapid suburban growth in Cincinnati, the Lakota School District quickly became the district of choice. Today it is one of the largest school districts in the state of Ohio encompassing 23 schools of K-12 in 63 square miles. In the 2020-21 school year, the Public School Review stated that Lakota school’s student body is 64%, White students. In addition, Lakota has a 93% graduation rate and is ranked in the top 20% of reading and math proficiency in the state of Ohio (Public School Review, 2021).

The fall of 2021 brought a new season of tension and turmoil with the introduction of political extremism to the district board. In a continuation of the White flight, political extremists joined the board member to stir narratives that our country has seen in the past to continue school segregation. These extremists have spoken against SEL, made claims Lakota Schools is teaching CRT, and have made efforts to discontinue the district’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion team. Lakota’s LODI team’s (Lakota Outreach Diversity Inclusion) mission per their website states:

In support of a thriving district climate and culture of excellence, the Lakota Outreach, Diversity, and Inclusion Department seeks to promote a welcoming and equitable experience and a culture that values diversity in all its forms through inclusive dialogue, interpersonal experiences, intercultural appreciation, and targeted professional development. – Lakota LODI team.

In addition, their website states, “Lakota Local Schools will actively engage all families, so they are seen, heard, and included in school communities, with the intent for all students’ success.”

With a significant wealth gap compounded with psychological challenges consequently, instituting a team to help promote equity and growth is imperative for the success of those who are suffering a scarcity of basic survival needs.

Another historical means of continuing segregation in Lakota School District, as in others, is actively advocating district-wide for Ohio House Bill 290, or the “Backpack Bill” (House Bill 290, 2023). Offering school vouchers is rooted in segregation that began in 1959-60 after Brown v. Board when the school board of Prince Edward County cut spending and did not levy taxes, which was the primary funding for integrated public schools. Instead, they offered vouchers to families while private citizens raised building funds to operate private schools. This consequently led to the closing of their entire public school system, leaving many families of color going to incredible lengths to educate their children. Despite the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the White flight to private academies allowed for a disproportionate number of White students to be enrolled. In 2019, among the 4.7 million K–12 students who were enrolled in private schools in fall, about 66% were White, 12% were Hispanic, and 9% were Black (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). Indiana’s voucher program is an example of the increased benefits for higher-income White students, many of whom are already in private schools, and diverts funding from all other students who remain in the public school system. Around 60% of voucher recipients come from White families, an increase of 14% since the program’s inception in 2013. The percentage of Black students receiving vouchers has dropped to 12%, down from 24% in 2013 (Turner, 2017).

Unfortunately, the efforts to continue the White flight and segregation of schools do not end with the extremists on the Lakota School Board, it is in much of the United States where sub groups of lawmakers are opening doors for history to systematically repeat itself. With the resignation of the Lakota superintendent in 2023, whom in 2022 received the prestigious national award of EmpowerED Digital Superintendent of the Year, the White flight continues to starve the district of talent and resources needed to continue it’s high ratings. History is repeating itself in Lakota schools with it’s inability to fill the Superintendent position, chipping away at talent and programing that draws in funding from taxpayers. This system of hording capital to prevent people of color from thriving is the continuing norm in Lakota schools, and around the nation.

*For more information regarding Lakota Schools and the former superintendent’s resignation, view here.

Higher Education, PWI’s and HBCU’s

There are numerous obstacles and barriers at all levels that BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students must continue to face within the higher education arena. Many interest groups and individuals across the nation, under the distorted slogan of “colorblindness,” have mounted relentless attacks against affirmative action and the existence of programs that attempt to provide much-needed equity for the prior intentional exclusion of BIPOC students from Predominantly White Institutions (PWI’s). In the 1960s and 70s integrated college enrollment saw a surplus (Harvey, 2004). The maturation of the Baby Boomer generation as well as the increased financial aid availability played a role however White women benefited disproportionately over their Black and Hispanic counterparts. In 1995, 6 million women, the majority of whom were White, had jobs they would not have otherwise held but for affirmative action (Wise, 1998). HBCUs have been the saving grace regarding accessing higher education. Since their inception, the HBCUs have been the foundation on which the “talented tenth” of the African American community’s civic, political, and social leadership has been developed (Harvey, 2004). Segregation resulted in the enrollment of the best and brightest of the African American community in the HBCUs, and the long list of notable individuals who received their baccalaureate degrees from HBCUs. In addition to HBCUs, community colleges emerged in response to the increasing interest in higher education among the American population. They reflected a shift away from the selective, even elitist, perspective that many four-year colleges and universities tended to embody. Community colleges were higher education institutions that could be attended by anyone who possessed a high school diploma, or a general equivalency diploma, which made them accessible to many individuals who would not have been able to meet the more stringent academic requirements for admission to four-year institutions. Community colleges also tended to be less expensive, and the colleges were frequently located in settings that made them more accessible than four-year colleges and universities making them very popular for BIPOC students.

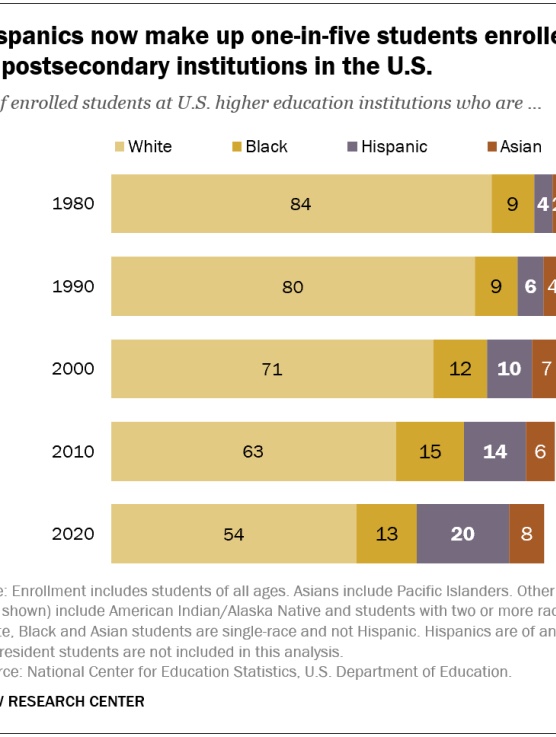

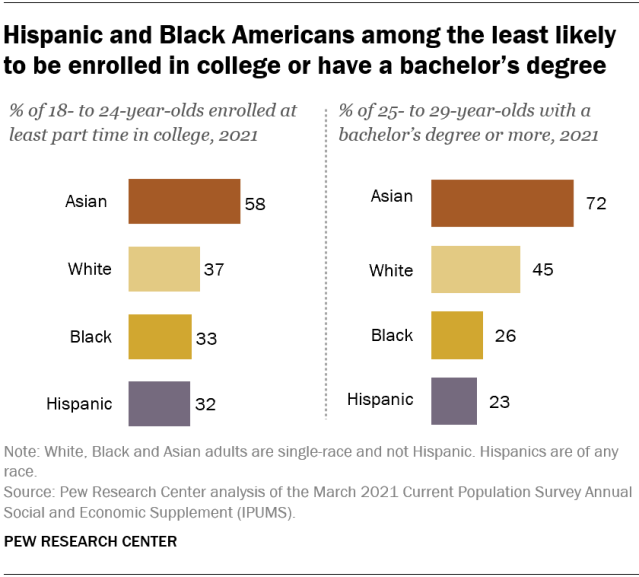

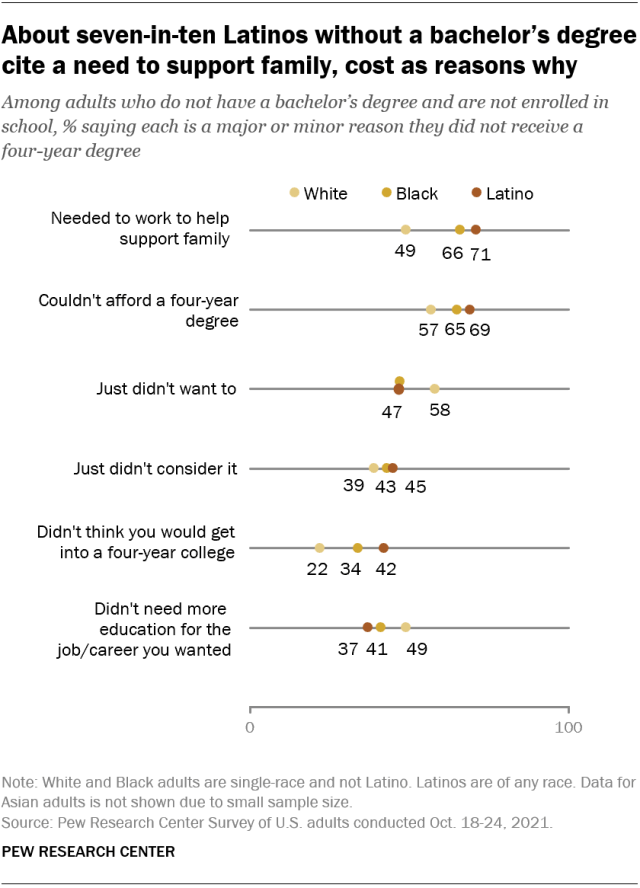

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a decline in postsecondary enrollment among LatinX and most other racial and ethnic groups. In the fall of 2020, there were 640,000 fewer students, including nearly 100,000 fewer LatinX, enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities than in the previous year. In 2021, about a quarter of LatinX ages 25 to 29 (23%) had earned a bachelor’s degree, up from 14% in 2010. A similar share of Black Americans in this age group (26%) had obtained a bachelor’s degree, while 45% of White Americans and 72% of Asian Americans ages 25 to 29 had done so. Minorities face many challenges that prevent the completion of a four-year degree more than their White peers.

Consequences due to the wealth gap stemming from the White flight, play into the significantly disproportionate number of BIPOC students. A rise in minority graduates at higher-level PWI institutions would require a significant systemic change to accommodate students’ deficiencies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the historical, sociopolitical, and psychological consequences of the White flight have led to a wealth gap that has yet to see long-term change. Our country still operates on systems of discrimination, income disparities, and redlining depriving our students of color of equal opportunity for education and success. Our children of color are susceptible to less funding, high dropout, and low graduation statistics. We the people need to consider a steady flow of conscious conversations, listening, educating, and understanding those who are living with consequences of generational disparity, marginalization, and lack of opportunity. The first step is knowing, the second is acknowledging, the third is intentionally living in community, and finally, leveraging capital to offer not only basic needs, and also, education. As a country, we need to reconsider an inclusive wholistic approach to education. Americans, in our entirety, would benefit from acknowledging these factors to enrich life for all races, strengthen our curriculum, and as a result, lead to better economic opportunities. Working together to provide equity to our most disparaged groups will significantly grow our collective GDP allowing for an equal means for all Americans to achieve self-actualization.

Citations

Alvord, M. K.; Grados, J. J., (2005). Enhancing resilience in children: a proactive approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(3), 238–245.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Biles, R; Mohl, R. A; Rose, M. H. (2014). Revisiting the urban interstates: Politics, policy, and culture since World War II. Journal of Urban History, 40(5), pp. 827-830.

Blakemore, E. (April 20, 2021). How The GI Bill’s Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans. A&E Television Networks, LLC.2023

Boustan, L. P.; Margo, R. A. (2013). A silver lining to white flight? White suburbanization and African–American homeownership, 1940–1980, Volume 78.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Madeline Will https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b616a81d3f720ccbe8c036d8e7f261f4a0856771

Bracey, E. N. (April 25, 2017) .https://doi-org.uc.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/ajes.12191

Brooker, R. (2022). The Education of Black Children in The Jim Crow South. American Black Holocaust Museum. 2022 https://www.abhmuseum.org/education-for-blacks-in-the-jim-crow-south/

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

Census.gov /America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2022

Census.gov /Publications /Income in the United States: 2021

Chamberlain, A.; Yanus, A. (2022) An “urban voluntary association” in the rural South? Urbanity, race, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, 1910–1930, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10:5, 767-787, DOI: 10.1080/21565503.2021.1906284

Champagne, A. M. (1973). The Segregation Academy and the Law. The Journal of Negro Education, 42(1), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/2966792

Child & Youth Services. (2021), VOL. 42, NO. 1, 24–42 https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1818558

Collins, W. J., & Shester, K. L. (2013). Slum Clearance and Urban Renewal in the United States. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(1), 239–273. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43189425

Democracy Docket. (Jan. 30, 2023). 2020 Redistricting Cycle Report: How Maps Were Challenged in Court. Democracy Docket 2023 https://www.democracydocket.com/analysis/2020-redistricting-cycle-report-how-maps-were-challenged-in-court/

Federal Register, 1/19/2023. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/19/2023-00885/annual-update-of-the-hhs-poverty-guidelines

Giles, M. W.; Gatlin, D. S.; Cataldo, E. F. (1974). The impact of busing on white flight. Social Science Quarterly, 55(2), 493–501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42859377

Hartman, T. (Oct 2, 2022). The War on Education: How Dismantling Public Schools Further Divides American into a Caste System. Milwaukee Independent. Milwaukee Independent LLC. 2023 https://www.milwaukeeindependent.com/thom-hartmann/war-education-dismantling-public-schools-divides-americans-caste-system/

Harvey, W. B., King, M. (2004) The Journal of Negro Education; Washington Vol. 73, Iss. 3: 328-340.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050305

Hug, F.; Degen, T.; Meurs, P.; Fischmann, F (2022). Psychoanalytical Considerations of Emotion Regulation Disorders in Multiple Complex-Traumatized Children—A Study Protocol of the Prospective Study MuKi. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022; 16: 809616. Published online 2022 Apr 26. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.809616

Irvine, R. W. (1983). “The Impact of the Desegregation Process on the Education of Black Students: Key Variables.” The Journal of Negro Education 52, no. 4 (1983): 410-22. doi:10.2307/2294948.

JocoMuseum. April, 28, 2022. The FHA and Suburbia. WordPress.com 2023

Kingkade, T.; Hixenbaugh, M. (2021). Parents protesting “critical race theory” identify another target: Mental health programs. NBCnews.com. NBC, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/parents-protesting-critical-race-theory-identify-new-target-mental-hea-rcna4991

Khan, M. M. (1963). The concept of cumulative trauma. Psychoanal. Study Child 18 286–306. 10.1080/00797308.1963.11822932

Lakota Online. 2023 https://www.lakotaonline.com/departments/students/lakota-outreach-diversity-inclusion-lodi

Leffler, W. K. (1963), U.S. News & World Report : Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 11 June 1963 https://iowaculture.gov/history/education/educator-resources/primary-source-sets/school-desegregation/governor-george

McGhee, H. (2021) The Sum of Us. New York, NY : One World, ©2021

McKown, C.; Gumbiner, L. M.; Russo, N. M.; Lipton, M. (2009) Social-Emotional Learning Skill, Self-Regulation, and Social Competence in Typically Developing and Clinic-Referred Children, Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38:6, 858-871, DOI: 10.1080/15374410903258934

Maslow, A. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological review 50 (4):370–396

Michas, F. (March 23 2023). Percentage of births to unmarried women in the U.S. 1980-2021https://www.statista.com/statistics/276025/us-percentage-of-births-to-unmarried-women/

Mohl, R. A. (2008). The interstates and the cities: The U.S. Department of Transportation and the freeway revolt, 1966-1973. The Journal of Policy History, 20(2), pp. 193-226.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Private School Enrollment. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgc.

Ohio School Report Cards. Cincinnati Public Schools, District Overview. 2023, https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/043752

Plessy vs. Ferguson, Judgement, Decided May 18, 1896; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States; Record Group 267; Plessy v. Ferguson, 163, #15248, National Archives.

Poussaint, A. F. (1979). White Manipulation and Black Oppression. The Black Scholar, 10(8/9), 52–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41163859

Public School Review, 2023. Cincinnati Public Schools School District. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/ohio/cincinnati-public-schools-school-district/3904375-school-district

Public School Review, 2021. Lakota Local School District. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/ohio/lakota-local-school-district/3904611-school-district

Reller, S. (2011). T. M. Berry Project: Berry and the Fight for Fair Housing in Cincinnati, Part 3. WordPress, 2011 https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2011/07/t-m-berry-project-berry-and-the-fight-for-fair-housing-in-cincinnati-part-3/

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)

The Tennessee State Museum (2014). An African American community’s fight over I-40. The Tennessee State Museum. Retrieved 12 November 2014 from http://www.tn4me.org/sapage.cfm/sa_id/248/era_id/8/major_id/12/minor_id/9/a_id/172.

Turner, C.; Weddle, E,; Balonon-Rosen, P. (May 12, 2017) “The Promise And Peril Of School Vouchers,” National Public Radio, May 12, 2017, available at http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/05/12/520111511/the-promise-and-peril-of-school-vouchers?utm_source=twitter.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npred&utm_term=nprnews&utm_content=20170512

Tjaden, P.; Thoennes, N (1998). Report No: NCJ 172837. Washington DC: US Department of Justice, OJP; 1998. The Prevalence, Incidence and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey

Tyack, D., and Robert Lowe. “The Constitutional Moment: Reconstruction and Black Education in the South.” American Journal of Education, vol. 94, no. 2, 1986, pp. 236–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1084950. Accessed 20 Mar. 2023.

U.S. Census Bureau (2020). 2020 Census. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/2020-census-main.html

U.S. Court of Appeals Sixth Circuit (1968). Nashville I-40 Steering Committee, Etc., et al., Plaintiffsappellants, v. Buford Ellington, Governor, et al., Defendants-appellees. Justia. Retrieved 22 September 2014 from http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/387/179/262311/.

Will, M. (May 14, 2019). 65 Years After “Brown v. Board,” Where Are All the Black Educators? EducationWeek. 2023

Wise, T. (1998). NWSA Journal; Baltimore Vol. 10, Iss. 3, (Fall 1998): 1-26. DOI:10.2979/NWS.1998.10.3.1

Ye, Y. (2007). Black initiative in black education prior to and during the civil war (Order No. 3280237). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304805593). Retrieved from https://uc.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fdissertations-theses%2Fblack-initiative-education-prior-during-civil-war%2Fdocview%2F304805593%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D2909